Recommendations for immediate and long-term strategies to reduce the environmental impact of freight

As the largest single contributor of greenhouse gases, the UK transport sector faces an urgent need to decarbonise

With a target to be net-zero on all greenhouse gases (GHG) by 2050, the UK faces an urgent need to reduce GHG across all industries. The transport sector accounts for 28% of CO2 emissions in the UK (Department for Transport, 2020) which is the largest contribution by a single sector. The sector is now facing pressure to completely decarbonise across all modes, for passenger and freight services, in order to meet the nationwide net zero commitment. Without increasing the capacity and attractiveness of rail freight or incentivising more environmentally friendly technologies, the UK transport industry will not reach its net-zero targets by 2050.

Whilst we are seeing praiseworthy developments in the sustainability of passenger transport through electrification, adoption of battery technology, trialling of hydrogen-powered trains and buses, there has been relatively little advancement in the decarbonisation of freight transport, due in part to a highly fragmented sector with no significant leadership or industry-wide representation on improving its environmental impact.

The UK still relies heavily on road services to transport its freight despite evidence showing that rail freight is cheaper and produces nearly nine times less CO2 per tonne-km than by road (Appendix A). A cohesive plan to improve the attractiveness and capacity of the UK rail network could drive a significant shift in mode share generating economic gains for freight customers and significant environmental benefits, with each freight train capable of removing 76 HGVs from the roads (Network Rail, n.d.). The mode share of rail is currently 9% (Department for Transport, 2020), but The Hub – Transport Advisory’s analysis shows that if rail achieved 30%, mode share of the freight industry then CO2 emissions would fall by at least 11%.

Our freight network is the UK’s economic musculoskeletal system and critical to economic growth and levelling-up across the country. The Covid-19 pandemic has demonstrated its importance and our national dependency on it, with a relatively minor impact on movements compared to passenger demand, which dropped to 20% of pre-Covid-19 levels. With post-pandemic travel behaviours set to change, the industry has a unique opportunity to reset and refocus on how we use our national transport networks, particularly for freight (which is less susceptible to reduction in emissions by changing behaviours), and make significant strides forward in decarbonising freight and logistics networks and operations.

The Hub – Transport Advisory has identified a range of action-oriented recommendations that could put the UK freight industry in the driving seat in transitioning us to a Net Zero economy:

- Creation of a new governmental national freight body with a refreshed accountability and focus on sustainable freight growth, and suitably funded to do so.

- Grant schemes to encourage research into smart technologies and implementation of digital innovations, e.g., ERTMS (European Rail Traffic Management System).

- Increased investment in intermodal facilities, particularly rail – maritime at ports, to bring them to the same standard as Felixstowe, Britain’s busiest port for rail freight.

- Modernise the Mode Shift Revenue Support (MSRS) scheme to better incentivise freight operators and their customers to choose rail and/or maritime over road.

- Create a requirement for the ORR to mandate that a fixed proportion of the capacity created by opening HS2 be reserved for freight services.

- Incentivise FOCs and leasing companies to transition away from diesel to more sustainable fuel options, for example by using electric Heavy Goods Vehicles (HGVs) – for last-mile services that cannot be completed by rail.

Freight accounts for over 40% of the transport sector’s emissions, which have been steadily growing over the past 30 years

Whilst GHG emissions have been falling steadily over the last 30 years, with a decrease of 45.5% between 1990 and 2018 (Department for Transport, 2020), this is largely credited to the decommissioning of power stations. The transport sector has not seen decreases in CO2 emissions in line with other sectors.

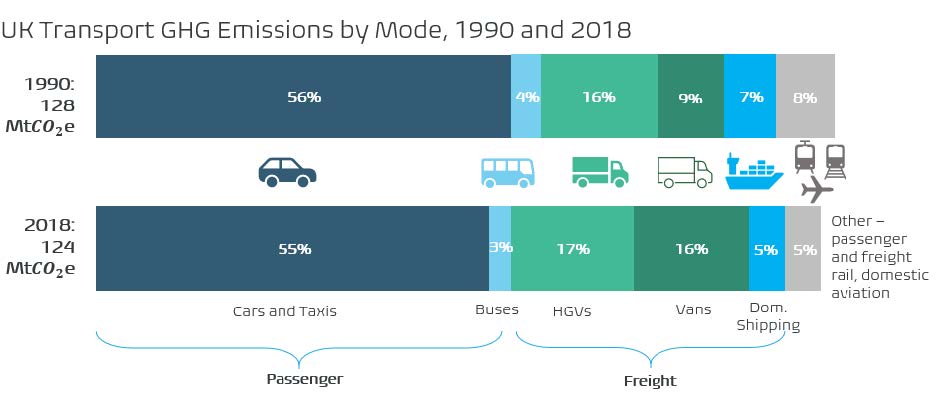

Figure 1: UK Transport GHG emissions by mode, 1990 and 2018 (Department for Transport, 2020)

In 2018, freight accounted for over 40% of the transport sector’s GHG emissions (49 MtCO2e) in the UK. With freight sector emissions growing by 6 MtCO2e between 1990 and 2018, the UK has never seen a decline in emissions from the sector and steps need to be taken to see reductions. (Department for Transport, 2020) Whilst client behaviours for passenger transport are beginning to become more environmentally conscious, this has not been the case with freight. There are immediate and long-term changes that can be made to the freight industry to reduce CO2 emissions of the transport sector, which are discussed in this report.

Two levers for Freight Decarbonisation

There are two overarching levers for reducing the environmental impact of freight:

1. Cleaner Energy: alternative energy sources, electrification, and de-dieseling to reduce GHG emissions per ton-km of all modes of transport but particularly road; and

2. Modal Shift: Move road freight to the more sustainable modes of maritime or rail.

1. Cleaner Energy

The maiden journey of a hydrogen train in the UK last year (Porterbrook, 2020) provides hope for the long-term future of a decarbonised rail industry. However, in the short term, the widespread use of electric trains and vehicles in the transport industry is more likely. We expect to see a cascade of electric locomotives previously used for passenger trains begin to be used for freight (Walton, 2020), which will drive significant improvement in rail freight decarbonisation.

Electric HGVs are also on the cusp of becoming mainstream. Since most freight journeys require first/last-mile services by road, the introduction of electric HGVs will be crucial to eliminating GHG for full end to end freight movements, even where freight is transported over long distances via maritime or rail. Companies such as Tesla, Ford and Daimler are all developing electric HGVs with promising distance ranges of up to 300km (Commercial Fleet, 2018). With the right support and financial incentivisation, electric HGVs can become the norm in the UK.

There are still some barriers to introducing electric HGVs and replacing the 501,500 HGVs (Department for Transport, 2020) in the UK with electric models, as this will take a considerable amount of time and funding. In the meanwhile, this would not decrease the proportion of freight transported by road, the mode emitting the largest amount of GHG. This means another method of reducing GHG emissions in the short term is required, namely through modal shift.

2. Modal Shift

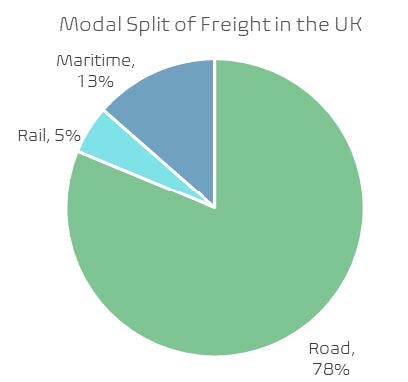

With 78% of freight being transported by road (the most environmentally damaging mode) the simplest way to kickstart decarbonisation would be to shift road freight to rail or maritime. However, the limited accessibility of maritime across most of the country means that the focus must be on shifting freight to rail. An average freight train is able to take 76 HGVs off the road (Network Rail, n.d.) – small changes to allow more freight trains to travel on the network would deliver substantial decreases of HGVs on the roads.

Figure 2: Modal Share of Freight (Department for Transport, 2020)

Mode Shift Scenario Analysis – The Environmental Impact of Rail Achieving 30% Mode Share

Rail Freight Forward is an existing coalition of Freight Operating Companies (FOCs) based in the UK and Europe, promoting a mode-share target of “30 by 2030”, which aims to have 30% of freight being transported by rail before 2030. (Rail Freight Forward, 2018) In this case study we demonstrate the potential level of savings from reaching this target:

Hypothesis: Achieving “30 by 2030” will enable GHG emissions from freight transport to decrease for the first time.

Results: Our assessment shows that achieving the “30 by 2030” goal will decrease GHG emissions by 11% (5.24 MtCO2e), demonstrating the power of modal shift

Mode Shift Scenario Analysis – The Case to Move More Freight from Road to Rail

Rail freight is cheaper for longer distances – so why does it not have a higher mode share? Not all road freight journeys in the UK may be suitable to be replaced by rail. Due to the dependence of road for first/last mile services, FOCs may choose to transport freight entirely by road. However, our assessment shows that, accounting for the additional impact of modal change for first/last-mile services, there is still road freight in the UK suitable for transport by rail which would also be cheaper.

- Figure 3 shows that up to a distance of 160km, road transport is cheaper than rail.

- Beyond 160km, the cost of rail is lower than the cost of road, even accounting for the cost of modal change for first/last-mile services.

- In the UK, this optimal distance D1 is considered to be 160km, just under the distance from London to Birmingham. (Simpson, 2018)

- In 2019, nearly 25% of freight carried on HGVs was hauled over 160km (Department for Transport,

- 2019), (Appendix B).

- The majority of these HGV movements could be replaced by rail services.

- Moving this quantity of freight to rail would enable rail’s mode share in the UK to increase to at least 28.5%, ever closer to “30 by 2030”.

There are significant barriers in the UK to shifting road freight to rail

Evidence shows that rail freight is cheaper than road (Austin, 2015), and produces nearly nine times less CO2 per tonne-km than road (European Environment Agency, 2017), (Appendix A). However, despite the availability of freight to move off the roads and onto the rail network, these benefits of using rail over road are not being harnessed to their full potential, due to a range of commercial and operational barriers – discussed below:

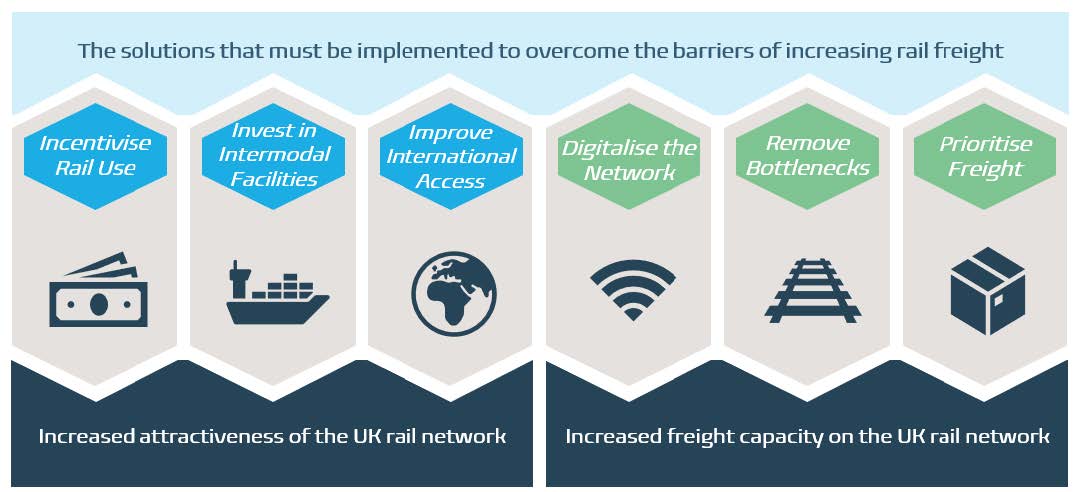

Figure 4: Diagram illustrating the solutions to overcoming the barriers of moving more freight onto the UK rail network

Increase the attractiveness of the network

Incentivise Rail Use

The need for first/last-mile services by road for most freight journeys reduces the attractiveness of rail over road. However, this can be counteracted with financial incentives to choose rail such as through the Mode Shift Revenue Scheme (MSRS). This will encourage FOCs to choose rail over road for their freight services.

Invest in Intermodal Facilities

Encouraging FOCs to move freight from maritime to rail instead of to road means investments are required into intermodal facilities, particularly at ports. Recent investments into intermodal rail connections at the Port of Felixstowe have seen a total of one million TEU of containers transported annually via rail, which saves 100 million HGV miles. This investment has allowed Felixstowe to become the busiest rail freight port in the UK, with 29% of freight shifting between maritime and rail. (The Port of Felixstowe, n.d.)

Improve International Access

There is limited standardisation in rail across Europe. Differences in track gauge require gauge changing facilities. Furthermore, different signalling systems often cause lengthy delays at borders caused by locomotive swaps. The UK should continue to implement ERTMS, a standardised signalling technology, to allow this to stop discouraging customers from using rail to bring freight into the UK. Alternatively, the use of multi-system electric locomotives also provides a usable solution to this problem.

Increase freight capacity on the network

Digitalise the Network

The UK currently has one of the least digitalized rail networks in Europe, this directly reduces the capacity of the network. To overcome this, the implementation of smart technology such as in-cab signalling and traffic management systems needs to progress quicker. This will help automate aspects of the network, consequently increasing capacity, as more trains will be permitted to safely pass through sections of the network per hour.

Remove Network Bottlenecks

The UK has a number of bottlenecks on its rail networks, particularly effecting freight trains travelling to ports such as Felixstowe and towards the Channel Tunnel. Whilst minor capacity increases can be achieved through digitalisation regarding these bottlenecks, new lines must be constructed to achieve a major capacity increase. Projects such as High Speed 2 (HS2) will help to relieve (freight) capacity on the existing network with more passenger trains moving to newly created high-speed lines.

Prioritise of Freight

Passenger services are usually prioritised when train slots are assigned to train companies. FOCs require better representation in the transport sector. In recent years, freight companies, among which GB Railfreight (GBRf), have been vocal in demanding change in the rail industry, seeking more consideration and prioritisation when decisions are made about the network (Walton, 2020). During the Covid-19 pandemic, as passenger numbers plummeted, rail freight demand fell no lower than 80% of usual figures. Rail freight was vital in transporting essential goods across the country quickly and sustainably. In considering future track access allocation, the economic value of rail freight transport should be assessed more comprehensively, and longer-term industry-wide strategies for rail freight are required. A national rail body (‘guiding mind’) for the rail industry should have the ability to take such an integrated view, balancing the requirements of passenger and freight transport.

Each of these solutions plays an important role in enabling more freight to travel along the UK rail network, and could simultaneously drive the sector to lower costs and GHG emissions.

The UK lags behind other European countries in its rail freight share

Whilst the UK has struggled to increase the mode share of rail in freight transport, other countries in Europe record higher proportions of freight transported by rail (Table 3).

These countries have adopted a range of initiatives to increase capacity for rail freight and achieve their environmental targets.

The UK lags behind other European countries in its rail freight share Country | Modal share of rail for freight transport |

Switzerland | 35% |

Austria | 32% |

Germany | 20% |

Italy | 13% |

United Kingdom | 9% |

Learning from other European countries provides ideas and initiatives that can benefit UK rail freight

Grant Schemes

France and Germany have launched grant schemes: Fret Ferroviaire Français du Futur (4F) (Walton, 2020) and Future Rail Freight Transport (Leijen, 2020) respectively. These schemes broadly operate as follows:

- 4F is a coalition of major industry players aiming to double the proportion of freight transported by rail to 18%.

- Under the German scheme, the government has allocated 30 million euros per year until 31 December 2024 to make future-proofing changes to the network.

- Funds are granted to those with ideas to improve the quality of the network and therefore the quantity of freight moved by rail.

- A priority has been identified as improving intermodal hubs and facilities, simplifying modal change from maritime and road to rail, reducing the number of journeys made solely by road.

The success of such schemes in France and Germany provides an example that similar schemes in the UK would incentivise modal shift. They provide the option to improve the quality and quantity of intermodal facilities and improve capacity on the network.

Construction of new lines

Countries such as Sweden, which lead the way for environmentalism in Europe, are investing in new high-speed lines for passenger transport. An additional benefit is that this relieves pressure on bottlenecks on the network by increasing the number of tracks benefiting rail freight (Trafikverket, 2020). Sweden demonstrates how a ‘guiding mind’ body has the ability to balance the economic importance of freight and passenger transport by creating a network-wide strategy.

Embrace technology

Traffic management systems can create safer, more automated networks. They harness the power of data to create optimal timetables are increasing punctuality, benefitting the capacity of the network. Implementation of a sophisticated traffic management system in the UK would be a significant investment, but an easier way to improve capacity and reduce dependency on building new tracks.

What can the UK do to reduce the environmental impact of freight?

Given the barriers to moving more freight onto the UK rail network and the cost of implementing alternative fuel vehicles in the future, we propose the following recommendations to help the UK decarbonise the freight transport industry:

Introduce a new governmental national freight body with a refreshed accountability and focus on sustainable freight growth, suitably funded to do so

- This will provide an integrated network-wide approach to coordinating strategies and business plans to improve the network for freight.

- The needs of freight customers will be better represented and considered in the design of the future UK rail network.

- Stronger sectoral leadership will improve the level of access to the network and target capacity improvements increasing rail’s mode share within the UK freight industry.

Introduce grant schemes to encourage research into smart technologies for rail

- Research into smart technologies and the implementation of such technologies, alongside ERTMS, will improve the quality of the UK rail network to match the standard across Europe. As the reputation and performance of the network increases, customers will be more likely to choose rail to transport freight.

- Such technologies will automate some operational aspects of the network.

- Currently, capacity is the biggest constraint facing the UK rail network. Digitisation will increase the safety and capacity of the network allowing for more freight journeys without constructing new infrastructure.

Invest in intermodal facilities, particularly between rail and maritime at ports

- Having modern intermodal facilities at ports, such as those recently implemented at Felixstowe, will increase the speed at which freight can be transferred between modes.

- These time-saving facilities will benefit FOCs and customers with quicker operations.

Modernise the Mode Shift Revenue Support (MSRS) scheme and increase funding

- MSRS is an existing scheme that incentivises the use of rail and inland waterways over road by offering grants to cover the cost difference between rail/inland waterway and January 2021

Decarbonising Freight in the UK March 2021

- road. The benefit of this grant must be reflected in the customer cost, encouraging customers to also choose rail/inland waterway transport over road transport.

- In 2017, the government reduced the funding of this scheme by £4.5 million, the cost of removing over 200,000 HGV journeys from roads (Whiteman, 2017).

- Originally launched in 2010, the research behind this scheme is now outdated resulting in the scheme not reaching its full potential to better incentivise FOCs and their customers to choose rail and/or maritime instead of road freight services.

- Any modernisation must consider the challenges facing the network at the moment. This scheme in combination with upgrades to the network is a guaranteed method of increasing demand and use for rail freight services in the UK.

Create a policy or legal requirement for the ORR to mandate that a fixed proportion of the capacity created by opening HS2 be reserved for freight services

- The opening of HS2 will create additional capacity for 144 trains a day, which would carry the equivalent of over 2.5 million HGVs’ worth of freight per annum.

- Critically, Phase 1 of HS2 will create additional capacity between London and Birmingham – a distance of 225km – which is cost-effective for freight companies to choose rail for this journey.

- Currently, there is no legal requirement for this additional capacity to be prioritised for freight, the ORR cannot mandate a proportion to be allocated to freight services since they use contractual agreements as a basis for assigning slots.

- The Government must create a policy or legal requirement for a proportion of free capacity to be used for freight.

- If implemented, rail freight is forecasted to grow by 3% each year until 2033, a 32% increase overall. (Logistics UK, 2020)

Incentivise FOCs and leasing companies to transition from diesel to more sustainable options. For example, by using electric HGVs – once they become more widely used – for first/last mile services that cannot be completed by rail

- In many cases first/last mile must be completed by road, due to the lack of access by other modes. In these cases, completing this section of the journey by an electric vehicle instead of diesel or petrol can reduce the GHG emissions of the journey considerably.

- As electric HGVs become more commonplace in the UK, the government must incentivise the procurement of electric vehicles over their counterparts as they will be more expensive and have more weight and distance restrictions making them less appealing.

Without increasing the capacity and attractiveness of rail freight or incentivising more environmentally friendly technologies, the UK transport industry will not reach its net-zero targets by 2050.

References

Austin, D., 2015. Pricing Freight Transport to Account for External Costs. [Online] Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/workingpaper/50049-Freight_Transport_Working_Paper-2.pdf [Accessed 10th December 2020].

Commercial Fleet, 2018. Will electric trucks be in it for the long haul?. [Online] Available at: https://www.commercialfleet.org/fleet-management/will-electric-trucks-be-in-it-for-the-long-haul [Accessed 3rd March 2021].

Department for Transport, 2019. Goods lifted by type and weight of vehicle and length of haul: 2019. [Online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/898703/rfs0113.ods [Accessed 6th January 2021].

Department for Transport, 2020. Decarbonising Transport: Setting the Challenge. [Online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/932122/decarbonising-transport-setting-the-challenge.pdf [Accessed 6th January 2021].

Department for Transport, 2020. Domestic Road Freight Statistics, United Kingdom 2019. [Online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/898747/domestic-road-freight-statistics-2019.pdf [Accessed 8th March 2021].

European Environment Agency, 2017. Specific CO2 emissions per tonne-km and per mode of transport in Europe. [Online] Available at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/energy-efficiency-and-specific-co2-emissions/energy-efficiency-and-specific-co2-9 [Accessed 11th January 2021].

Eurostat, 2020. Modal split of freight transport. [Online] Available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=tran_hv_frmod&lang=en [Accessed 10th December 2020].

Leijen, M. v., 2020. Germany allocates 102 million euros for rail freight. [Online] Available at: https://www.railfreight.com/policy/2020/05/26/germany-allocates-102-million-euros-to-support-rail-freight/ [Accessed 18th December 2020].

Logistics UK, 2020. High Speed 2: The case for released freight capacity. [Online] Available at: https://logistics.org.uk/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=26280145-1894-452e-8f18-7193fc0a5646&lang=en-GB [Accessed 6th January 2021].

Network Rail, n.d. Rail Freight. [Online] Available at: https://www.networkrail.co.uk/industry-and-commercial/rail-freight/ [Accessed 6th January 2021].

Porterbrook, 2020. UK’s First Hydrogen Train takes to the Mainline. [Online] Available at: https://www.porterbrook.co.uk/news/uks-first-hydrogen-train-takes-to-the-mainline [Accessed 8th December 2020].

Rail Freight Forward, 2018. 30 by 2030: Rail Freight strategy to boost modal shift. [Online] Available at: https://www.railfreightforward.eu/sites/default/files/downloadcenter/whitepaperldupdated.pdf [Accessed 11th December 2020].

Simpson, M., 2018. Replace road haulage with rail freight, what is the solution? [Interview] (22nd March 2018).

Thales, 2020. Traffic Management Systems. [Online] Available at: https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/countries/europe/germany/transportation/traffic-management-systems [Accessed 16th February 2021].

The Geography of Transport Systems, n.d. Distance, Modal Choice and Transport Cost. [Online] Available at: https://transportgeography.org/contents/chapter5/transportation-modes-modal-competition-modal-shift/transcost/ [Accessed 10th December 2020].

The Port of Felixstowe, n.d. Port of Felixstowe is Britain’s Biggest and Busiest Rail Freight Port. [Online] Available at: https://www.portoffelixstowe.co.uk/port/rail-services/ [Accessed 3rd March 2021].

Trafikverket, 2020. A new generation railway – new main lines for high-speed trains. [Online] Available at: https://www.trafikverket.se/en/startpage/planning/high-speed-railway/ [Accessed 16th February 2021].

Vivid Economics, 2019. The Value of Freight. [Online] Available at: https://nic.org.uk/app/uploads/Future-of-Freight_The-Value-of-Freight_Vivid-Economics.pdf [Accessed 8th December 2020].

Walton, S., 2020. French rail freight should double before end of decade. [Online] Available at: https://www.railfreight.com/railfreight/2020/06/19/french-rail-freight-should-double-before-end-of-decade/ [Accessed 18th December 2020].

Walton, S., 2020. More electric traction for UK freight. [Online] Available at: https://www.railfreight.com/railfreight/2020/05/20/more-electric-traction-for-uk-freight/ [Accessed 4th March 2021].

Walton, S., 2020. UK Freight Now Priority by Default. [Online] Available at: https://www.railfreight.com/railfreight/2020/03/25/uk-freight-now-priority-by-default/ [Accessed 5th January 2021].

Whiteman, A., 2017. Cut to UK rail freight grants will drive loads back onto the roads. [Online] Available at: https://theloadstar.com/cut-uk-rail-freight-grants-will-drive-loads-back-roads/ [Accessed 3rd March 2021].